Multimedia Journal of Metaverse in MEDICINE

CASE REPORT | JANUARY 2, 2025

An unusual phenotypic change in a rectal originated gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) after tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy: A case report with a brief review of the diagnostic pitfalls

Rong Yan1*, Peng Xia1

1 Department of Surgical Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an JiaoTong University, Xi’an 710061, China.

Corresponding Authors: Rong Yan. E-mail: [email protected]

Address: Department of Surgical Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an JiaoTong University, Xi’an 710061, China.

Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most prevalent mesenchymal tumor, typically KIT (CD117)-positive and responsive to targeted therapies. Herein, we present a unique case of a 62-year-old male diagnosed with rectal GIST. Core needle biopsy revealed a cellular spindle cell GIST with high expression of CD117, DOG-1, and CD34. The presence of four mitotic figures in ten high-power fields (HPFs) indicated a high-risk tumor. Notably, his immunophenotype underwent changes following imatinib treatment. Eight months after initiating imatinib therapy and complete tumor resection, histological examination revealed an extensive spindle cell population lacking dysplasia, resembling a solitary fibrous tumor. Immunostaining for CD117, and DOG-1 negative. To gain insights into the diagnostic challenges associated with immunophenotypic alterations in rectal GIST, we conducted a literature review and discussed the diagnosis and treatment of this condition. Recognition of this phenomenon is crucial to avoid diagnostic pitfalls when assessing post-treatment resection specimens from GIST patients.

Keywords: GIST; tyrosine kinase inhibitors; unusual phenotypic change; diagnostic pitfalls

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most prevalent nonepithelial neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract, marking a milestone in targeted therapy for solid tumors[1]. Although rare, their incidence accounts for approximately 3% of gastrointestinal malignancies. Notably, GISTs primarily occur in the stomach and small intestine, with rectal involvement being relatively uncommon, accounting for only 3 to 5% of cases[2].

The onset of rectal GIST is often subtle, lacking specific symptoms in the early stages. Surgical management is challenging due to the tumor’s location in the lower rectum, within a confined pelvic cavity, and the patient’s desire to preserve the anus. A recent study highlighted the high locoregional recurrence rate among rectal GIST patients following both local excision and extended surgery[3].

We present a noteworthy case of a rectal GIST patient who underwent eight months of imatinib therapy, yet tumor growth persisted. Subsequently, a rectal Miles surgery was performed, and the resected specimen was referred to our pathology department for analysis. Surprisingly, the immunohistochemical staining results postoperatively were discordant with the preoperative findings, posing diagnostic dilemmas.

This case underscores the importance of recognizing potential diagnostic pitfalls, particularly in the context of immunophenotypic changes in rectal GIST. Future studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these changes and their impact on patient outcomes.

Case Presentation

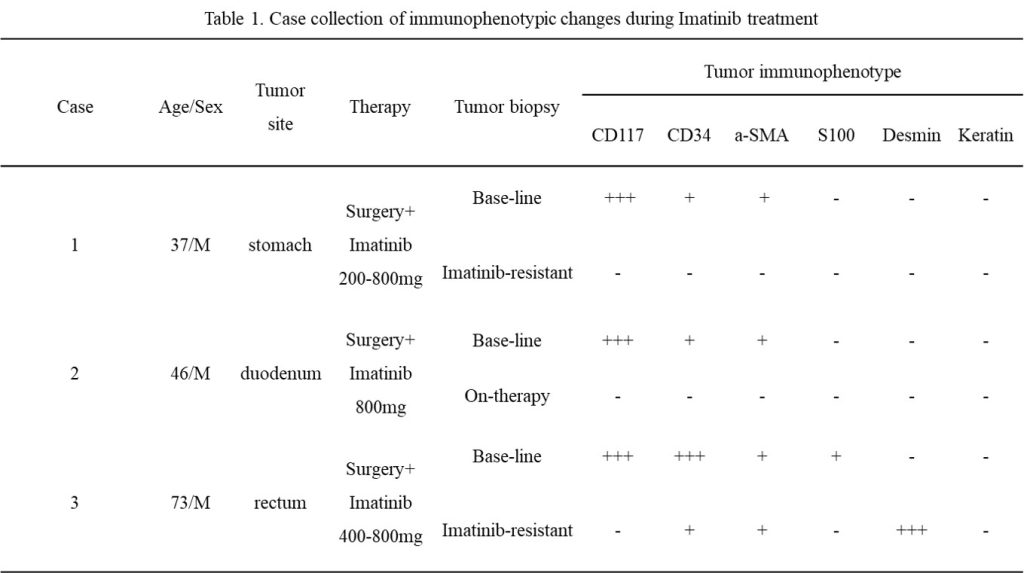

A 64-year-old male patient was hospitalized due to intermittent increases in stool frequency lasting seven years, with a one-year aggravation. Seven years prior, the patient experienced intermittent increases in defecation frequency without obvious inducement. accompanied by blood filaments, sometimes up to 10 times daily. Constipation and tenesmus were intermittent, with no abdominal pain, abdominal distension, chest tightness, shortness of breath, nausea, or vomiting. Pelvic CT on October 14, 2012, revealed space occupation by the anterior wall of the rectum, with an unclear boundary between the posterior wall of the prostate. Endoscopic ultrasonography on October 12, 2012, suggested a rectal protrusion, favoring a GIST. Biopsy pathology on October 22, 2012, confirmed a spindle cell tumor with immunohistochemical findings supportive of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (CD117+, CD34+, DOG-1+, H-caldesmon+, S-100-, SAM focal +, Desmin-; Figure 1). The patient declined imatinib therapy and genetic testing, and did not respond to unspecified Chinese herbal medicine treatment. By 2016, symptoms worsened, along with abdominal distension. Pelvic CT on October 10, 2016, at our hospital showed prostate calcification and a thickened rectal wall with a soft tissue mass consistent with stromal tumor characteristics. Pelvic MRI revealed a 60.0mm×86.6mm×67.8mm space-occupying lesion in the anterior wall of the rectum. Given its proximity to the anus (3 cm) and the patient’s condition, anus preservation during surgical resection was challenging. According to the NCCN guidelines and Chinese guidelines for stromal tumor diagnosis and treatment, initial treatment with imatinib is recommended.

Fig.1 Patient’s biopsy pathology & immunophenotypic (2012-10-22). Morphologically expressed as spindle-shaped cells, densely arranged. GIST-specific antibodies were positive in immunohistochemistry.

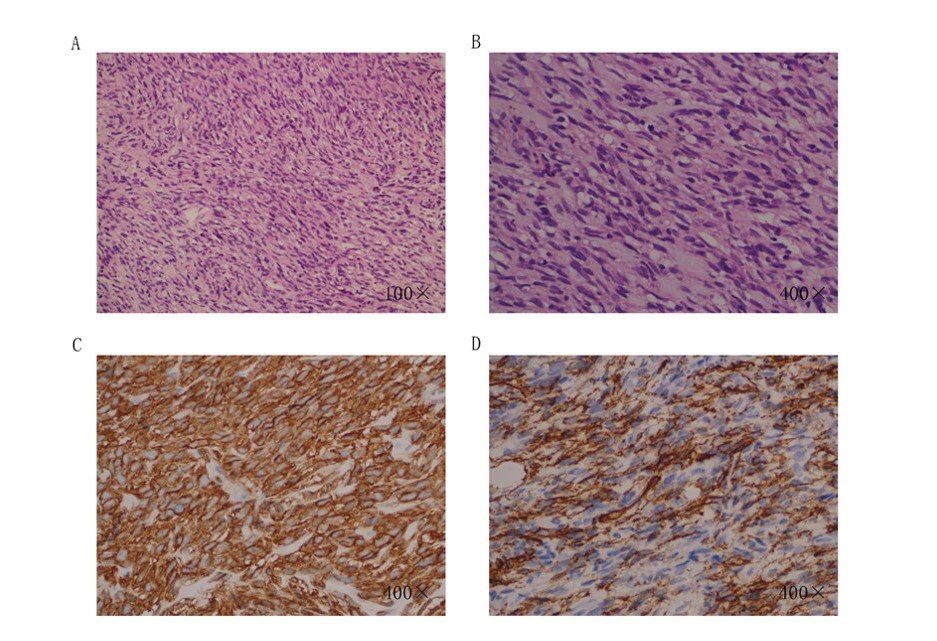

After taking imatinib for over 8 months, a Pelvic CT scan revealed an irregular mass in the lower rectal segment. Although smaller, it measured 60.0mm×46mm×48mm. Lymph nodes were also visible in the pelvic cavity. Despite this, the patient refused to undergo genetic testing, precluding any assessment of whether second-line medication like Sunitinib would be beneficial. Following an MDT meeting and completion of the necessary examinations to exclude contraindications, a Miles surgery was performed. Postoperatively, the rectal specimens were sent for examination. The rectum measured 19cm in length, with a diameter ranging from 3-6.9cm. The anal canal was 3cm long and 4cm in diameter. Nodular masses were observed in the rectal wall, located between 10cm from the upper resection margin and 2.5cm from the lower resection margin, measuring 6cm×4.5cm×4cm. Immunohistochemical staining revealed the following: spindle cell tumor tissue from the rectal wall, involving the lamina propria of the mucosa and focal anal canal tissue, suggest a diagnosis of “solitary fibrous tumor” based on the pattern of staining and the morphology observed. The immunostaining profile is characterized CO117(-), Dog(-), CD34(+), Bcl-2(focal +), SMA(-), Des(-), Caldesmon(-), CD99(-), S-100(-), GFAP(-), CD68(-), CK(-), Ki67(+1%). These findings suggest a spindle cell tumor of the rectal wall, involving the inherent stroma and focal anal tissue (Figure 2).

Fig.2 Patient’s surgical specimen pathology (2017-06). Expressed as interstitial, sparsely arranged spindle-shaped epithelial cells. GIST-specific antibodies were negative in immunohistochemistry.

The negative staining for CD117 and Dog-1 is notable as these markers are typically positive in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), which can be a differential diagnosis for spindle cell neoplasms in this location. The positive staining for CD34 is consistent with the immunohistochemical profile of solitary fibrous tumors, which often express this marker. The focal positive staining for Bc1-2 suggests the presence of some tumor cells expressing this apoptosis-regulating protein, which can be seen in a variety of tumor types.

The negative staining for SMA, Des, Caldesmon, CD99, S-100, GFAP, and CD68 helps to exclude other spindle cell neoplasms such as smooth muscle tumors, desmoid tumors, caldesmon-positive leiomyosarcomas, Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET), schwannomas, and histiocytic neoplasms, respectively. The low Ki67 proliferation index of 1% suggests a relatively indolent tumor with low proliferative activity, which is characteristic of solitary fibrous tumors.

Upon re-examination of the pathological specimen and consultation of related literature, we maintain our diagnosis of GIST. Given the patient’s high postoperative risk classification, we recommend continuation of oral imatinib intake and regular follow-up exams. No distant metastasis was observed until 2021, when the patient presented with multiple liver and lung metastases. Consequently, the patient then refused to continue with further follow-up.

Discussion

Rectal GIST is relatively uncommon compared to other types of GIST, which typically arise from Cajal cells. These tumors most frequently occur in individuals aged 50 years, predominantly in the stomach (60%), jejunum and ileum (30%), duodenum (4-5%), rectum (4%), colon and appendix (1-2%), and esophagus (1%) [4]. Rarely, they manifest as primary extragastrointestinal tumors located near the stomach or intestines.

In the present case, preoperative pathological findings indicated positivity for CD117, CD34, DOG-1, and H-caldesmon, with negativity for S-100, focal positivity for SAM, and negativity for Desmon. These results supported a diagnosis of rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. However, postoperative pathology presented contrasting findings: negativity for CO117, Dog, Bcl-2 (special mess), SMA, Des, Caldsmon, CD99, S-100, GFAP, CD68, CK, and positivity for CD34 and Ki67 (+1%). These findings suggested a diagnosis of solitary fibrous cancer.

One regrettable aspect of this case was the failure to re-examine histopathology before initiating imatinib treatment. Due to the absence of pathological clues, it was impossible to determine whether the patient’s pathological changes preceded or followed imatinib administration.

To elucidate the reasons for this discrepancy, we considered the following possibilities. We first discounted any differences that could be attributed to the use of different antibody lot numbers at various time points for the two specimens or human error in the antibody blocking and washing procedures. This was because operational errors are unlikely to cause such significant differences in immune phenotype.

Next, we rejected the hypothesis that the tumor in this patient was a combination of multiple tissue types. This was based on our literature review, which indicated that two distinct cancer types originating from the same location are exceptionally rare. Additionally, even after the patient took imatinib, the GIST subgroup was infrequently eliminated. Although the MRI indicated a significant reduction in tumor size following imatinib treatment, the rectal wall thickness increased. This finding does not support the notion that GIST cells were completely eradicated by the drug.

After eight months of imatinib chemotherapy, the most plausible explanation is that the tumor’s molecular phenotype underwent changes at the mRNA level. The concept of GIST dedifferentiation was first introduced by Pauwels et al. [5] to describe the transformation of tumors from classic CD117-positive to CD117-negative GIST. This phenomenon occasionally occurs during treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, either primarily or as a result of prolonged imatinib therapy. This change in both morphology and immunoprofile poses a diagnostic challenge for pathologists. Their study reported several patients with advanced GISTs who experienced complete phenotypic transformation during imatinib treatment.

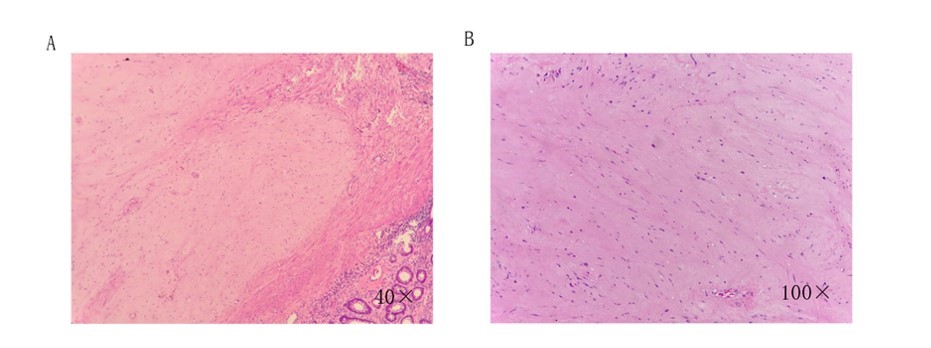

We have summarized the reported cases in Table 1 [5]. Notably, the loss of CD117 was accompanied by phenotypic alterations, including epithelioid morphology and the emergence of cytokeratin or desmin expression, or both [6, 7]. Clinically, dedifferentiated GIST is typically highly invasive and unresponsive to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

From an immunohistochemical perspective, a tumor with negative staining for both dog-1 and CD117 should be diagnosed as schwannoma if s-100 is positive or as a smooth muscle-derived tumor if SMA is positive. However, in cases where the histopathological features are compatible with GIST, but the immunohistochemical results for dog-1 and KIT are negative, and other immunohistochemical markers do not support a schwannoma or smooth muscle-derived tumor diagnosis, the diagnosis of GIST can be established if c-kit or PDGFRA gene mutations are detected. It is important to note that the absence of mutations in the c-kit and PDGFRA genes does not completely rule out the possibility of wild-type GIST.

In the present case, the preoperative pathology was typical of GIST, and the postoperative histopathological findings were consistent with GIST, ruling out schwannoma or smooth muscle-derived tumor. However, genetic testing was not performed during the treatment process, thereby leaving uncertainty regarding the presence of c-kit and PDGFRA gene mutations. Consequently, the possibility of wild-type GIST cannot be excluded. This underscores the importance of genetic testing before surgery and drug treatment to aid in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.

Several clinical trials [8-10] have demonstrated that neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate treatment for locally advanced primary GIST can enhance the duration of disease-free survival (DFS) among GIST patients. Additionally, IM treatment has the ability to modify tumor size and/or density, often leading to beneficial outcomes during surgical resection.

In the present case, the patient underwent imatinib treatment for eight months prior to surgery. Although clinical symptoms improved, the tumor size did not exhibit a significant reduction. Given its proximity to the anus (only 3cm), anal preservation was not feasible, and therefore, a Miles operation was performed. In a similar case reported by [11], a patient diagnosed with a large rectal GIST received preoperative imatinib for six months. This treatment reduced the tumor diameter from 8cm to 5cm, allowing for the performance of anal sphincter-sparing surgery.

These cases highlight the importance of considering neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate treatment for locally advanced primary GIST, as it can potentially improve surgical outcomes and increase the chances of anal preservation. However, it is also essential to individualize treatment plans based on tumor characteristics and patient-specific factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we encountered an exceptionally rare case of immunohistochemically variant large rectal GIST. The use of preoperative adjuvant treatment with imatinib mesylate was beneficial in facilitating surgical resection. However, the strategy for preserving the anus in such cases remains a topic of ongoing discussion and exploration among surgeons. Future research and clinical experiences are crucial in refining our understanding of the optimal management of these rare and complex tumors.

Author Contributions

Rong Yan wrote the first draft and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. Peng Xia reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Received: 11 October 2024

Accepted: 12 December 2024

Published on line: 2 January 2025

Reference

- Doran, Ksienski. Imatinib Mesylate: Past Successes and Future Challenges in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Clinical Medicine Insights: Oncology, 2017.

- Parab TM, et al., Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019, 10(1):144-154.

- Yasui, M., et al., Characteristics and prognosis of rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of registry data. Surgery Today, 2017. 47(10): 1188-1194.

- Miettinen, M. and J. Lasota, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology and prognosis at different sites. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology, 2006. 23(2): 70-83.

- Pauwels, P., et al., Changing phenotype of gastrointestinal stromal tumours under imatinib mesylate treatment: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Histopathology, 2005. 47(1): 41-47.

- Díaz Delgado, M., et al., Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Morphological, Immunohistochemical and Molecular Changes Associated with Kinase Inhibitor Therapy. Pathology & Oncology Research, 2011. 17(3): 455-461.

- Canzonieri, V., et al., Morphologic shift associated with aberrant cytokeratin expression in a GIST patient after tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy. A case report with a brief review of the literature. Pathology – Research and Practice, 2016. 212(1): 63-67.

- McAuliffe, J.C., et al., A Randomized, Phase II Study of Preoperative plus Postoperative Imatinib in GIST: Evidence of Rapid Radiographic Response and Temporal Induction of Tumor Cell Apoptosis. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 2009. 16(4): 910-919.

- Fiore, M., et al., Preoperative imatinib mesylate for unresectable or locally advanced primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO), 2009. 35(7): 739-745.

- Eisenberg, B.L., et al., Phase II trial of neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate (IM) for advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): Early results of RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2009. 99(1): 42-47.

- Liu JQ, Li XY, Yu HQ et al. Tumor-specific Th2 responses inhibit growth of CT26 colon-cancer cells in mice via converting intratumor regulatory T cells to Th9 cells. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 10665.

- Kramp, K.H., et al., Sphincter sparing resection of a large obstructive distal rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumour after neoadjuvant therapy with imatinib (Glivec). Case Reports, 2015. 2015(1):. bcr2014207775-bcr2014207775.